2014, President Obama expanded the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, making it the largest marine preserve in the world at the time. The expansion closed 490,000 square miles of largely undisturbed ocean to commercial fishing and underwater mining.

The preserve is nowhere near the mainland United States nor is it all in close range to Hawaii. Still, President Obama was able to protect this piece of ocean in the name of the United States.

To understand how the U.S. has jurisdiction over these waters in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, one has to look back to the 19th Century when, for a brief period, the U.S. scoured the oceans looking for rock islands covered in guano. That is: seabird poop.

Guano was a great fertilizer and many believed it would revolutionize farming, which traditionally involved cycling crops or simply depleting soil nutrients and moving to new land.

While novel to Americans and Europeans, using bird poop as fertilizer was nothing new to the Quechua people of Peru who had long mined it from the Chincha Islands off the southwest coast of Peru. For centuries, seabirds nesting on the islands had piled up guano, sometimes close to a 100 feet deep, making it a rich and ready source of the stuff.

Europeans hadn’t shown any interest in guano until the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt visited the Peruvian coast in 1804, and saw laborers unloading ships filled with seabird poop. Von Humboldt took a sample and brought it back to Europe. A German chemist named Justus Von Liebig subsequently began promoting a theory that soil fertility came down to a few critical nutrients—nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Peruvian guano was rich in all three.

Europeans hadn’t shown any interest in guano until the Prussian naturalist Alexander von Humboldt visited the Peruvian coast in 1804, and saw laborers unloading ships filled with seabird poop. Von Humboldt took a sample and brought it back to Europe. A German chemist named Justus Von Liebig subsequently began promoting a theory that soil fertility came down to a few critical nutrients—nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Peruvian guano was rich in all three.

It was the agricultural analogue to discovering gold

The Peruvians began to mine guano on a commercial scale. Their operations relied on an abusive labor system, first with locally coerced laborers and then with imported Chinese workers. Miners lived on the islands in tents and shacks, working up to 17 hours a day. The ages were low, and the conditions were awful; guano is acrid, and caustic when inhaled.

The guano trade made its way to Europe via British merchants, and soon farmers across the continent were using Peruvian guano on their fields. Word of the fertilizing power of seabird poop reached the United States, and by the late 1840s the country had entered a state of what historians have called “guano mania.” Tens of thousands of tons of guano were being imported to the U.S. every year.

British firms controlled the Peruvian trade, and guano was expensive. American interests resolved to break the monopoly. Entrepreneurs in the United States petitioned Congress to create a mechanism to help them claim their own guano islands. Some lawmakers opposed this effort, on the grounds that it smacked of the same kind of imperialism that various European countries were engaged in around the world at the time.

British firms controlled the Peruvian trade, and guano was expensive. American interests resolved to break the monopoly. Entrepreneurs in the United States petitioned Congress to create a mechanism to help them claim their own guano islands. Some lawmakers opposed this effort, on the grounds that it smacked of the same kind of imperialism that various European countries were engaged in around the world at the time.

The U.S., of course, already had its own approach to imperialism, having taken over much of North America by stealing territory from indigenous people. But political leaders didn’t think of this as imperialism, since these lands were incorporated into the country, first as territories and then as states.

Ultimately, a compromise was reached: the guano islands would not be considered as subject to the sovereignty of the U.S. but rather as “appertaining” to the United States. While few knew what this meant from a legal perspective, it was softer than claiming full ownership.

In 1856, the Congress passed the Guano Islands Act. Over the next several years U.S. companies claimed more than 70 islands throughout the Pacific and the Caribbean.

While the interest in guano declined as commercial fertilizers became available, the Guano Islands Act had set a legal precedent that would help justify future acts of American imperialism on islands that were, unlike the Guano Islands, very much inhabited.

While the interest in guano declined as commercial fertilizers became available, the Guano Islands Act had set a legal precedent that would help justify future acts of American imperialism on islands that were, unlike the Guano Islands, very much inhabited.

In 1898, following the Spanish-American War, the United States took possession of Puerto Rico, the Phillipines, and Guam, setting off a debate as to how these islands and their citizens would be treated. Statehood was seen as politically problematic — there was little interest in absorbing islands full of people of color as new territories or states, which left them in limbo.

By 1901, the issue of their status had reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The case raised the question: could the U.S. impose duties on a shipment of oranges from Puerto Rico to New York? The constitution prohibited these duties among the states but these were not states The court ruled that these duties were legal since Puerto Rico was “foreign in a domestic sense,” making it not fully part of the U.S. Some of the justices pointed to the Guano Islands Act as justification.

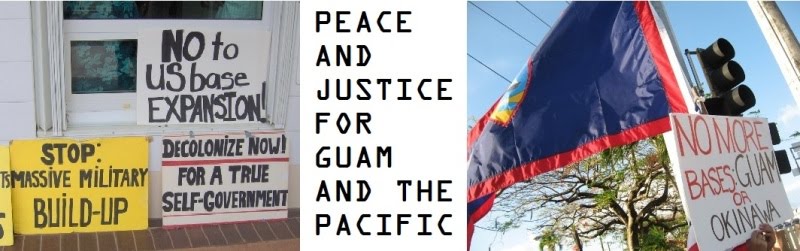

This has perpetuated a kind of limbo status for these territories that continues to be an issue. Puerto Rico, and other islands like Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Marianas are still “foreign in a domestic sense,” which has facilitated continuous U.S. control thereof, but without the U.S. providing all of the associated rights and privileges. Puerto Ricans, for instance, cannot vote in federal elections, but they are considered American citizens and can freely travel and work in the U.S.

This has perpetuated a kind of limbo status for these territories that continues to be an issue. Puerto Rico, and other islands like Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Marianas are still “foreign in a domestic sense,” which has facilitated continuous U.S. control thereof, but without the U.S. providing all of the associated rights and privileges. Puerto Ricans, for instance, cannot vote in federal elections, but they are considered American citizens and can freely travel and work in the U.S.

The U.S. still holds claim over a few of the old Guano Islands in the Pacific, although they go by a different name today: the United States Minor Outlying Islands. They don’t have any permanent residents, but these little rock islands are part of the American empire and thus provide the legal justification for President Obama’s creation of one of the largest marine reserves in the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment